It's December Days time again. This year, I have decided that I'm going to talk about skills and applications thereof, if for no other reason than because I am prone to both the fixed mindset and the downplaying of any skills that I might have obtained as not "real" skills because they do not fit some form of ideal.

12: George

I call it a habit of mine that I can make outdated hardware do things it may or may not have ever intended to do. "I" is not quite right in this statement, because much like how my cooking is following recipe and then being surprised that it turns out delicious, much of my computer touchery is following recipe that others have developed, and occasionally deviating from it if I need to for troubleshooting, or to mess about in the thing that the original creator said could be messed with or customized to meet the needs of the person using the software.

Much of the confidence and practice I have with computer touchery comes from having had a machine to experiment on, one specifically designated as the one that if things explode, I can reset back to a working state and then go forward from there. I don't actually want to have to do that kind of thing, because resetting an exploded machine usually means losing progress or having save files get nuked that I want to preserve, but there is a certain amount of risk affordance you can put on your spare machine that your main machine won't get. Spare machines are the best kinds of machines, usually put together from spare parts, or specific small parts that have been purchased to swap out from one thing to another. They're great for people who want to experiment or to learn how to assemble their own machines, or who want to try some other operating system. Everyone should have a spare machine somewhere along the way, preferably one they've assembled or that they've changed some components on, but single-board machines and spare phones are also ways of doing some amount of experimentation, even if you can't change their components quite so easily.

Spare machines are great for working through problems that arise when you do things. Like when I finally saved up enough money to purchase a 3dfx Voodoo2 3D rendering card. I thought I was going to be blazing hard through various games now, with my relatively unimpressive machine (it barely met the specs for Final Fantasy VIII!), but after I'd dropped it in, and tried to boot up my machine, having hooked it all up, the motherboard beeped at me and refused to boot. After a certain amount of troubleshooting, I finally figured out the thing that hadn't been obvious to me at the start: the 3dfx card was a companion to the video card I already had installed, and that other port on the 3dfx card wasn't for show - I needed a specific cable to take the output from my video card and feed it into the 3dfx card, and then after they'd daisy-chained their way merrily through the requirements, they gave me the output I desired. Which made Final Fantasy VIII playable. (And then I would have a bit of a time with the game wondering why I was seeing things like "B6" during Zell's Limit Break instead of the keyboard controls I wanted. Eventually I figured out that I needed to unplug the gamepad that I had connected to the machine and that it was detecting and assuming that I was playing the game on the gamepad primarily. This was back when discrete sound cards were a part of your rig, and they often also had a port on them for gamepad input.)

So I've done a lot with spare machines, tinkering, experimenting, and trying things with them that I wouldn't do to the "family computer" and that I wouldn't do to my work computer. My "spare" machines have proliferated in my adult life, as I continue to move things around and new machines enter my life. But also, so have my appliance machines. Instead of a full tower desktop running in the bedroom, I have a singe-board machine there. Much quieter and less of a power draw, still does all the desktop environment things I want (as well as some other things, like allowing me to remotely control the TV it's attached to, the one without a working IR receiver.) I definitely had a second machine for much of my time in the bad relationship, and for a time, I used a cell phone dock and some nice cabling to turn a single-board machine in to much more of a laptop. It could at least run XChat at a few other things at the time. A secondhand Surface I'd gotten from someone served as my "work" machine during the shutdown, before receiving an official work laptop. (That Surface eventually suffered from the batteries trying to burst forth from the casing and had to be retired, but we salvaged the SSD from it for purposes.) And I kept two desktops working side-by-side as soon as I reclaimed my house, so that one machine could be used for media purposes and Windows stuff, and the other could be used for Linux purposes and handling all the things I was doing with Android phones and other things where it turns out to be easier to do things from a terminal on a Linux box than it is in Windows. And since nothing "vital" was on the Linux box, I could experiment with it, change distributions, and otherwise use it as the spare that it was. This combined with the experience I had from using Linux as a driver since graduate school to make me comfortable enough to use Linux as the driver on my main machine as well. Something that started because one of my classes meant learning a little Ruby on Rails, and it's way easier to run a local Rails server from Linux than Windows has now come around to being a machine that I can watch streams on, game on (all hail Proton), and otherwise continue to give life to, since I wanted a machine that I could buy and hold as much as possible, instead of thinking I needed to change it from one thing to the next.

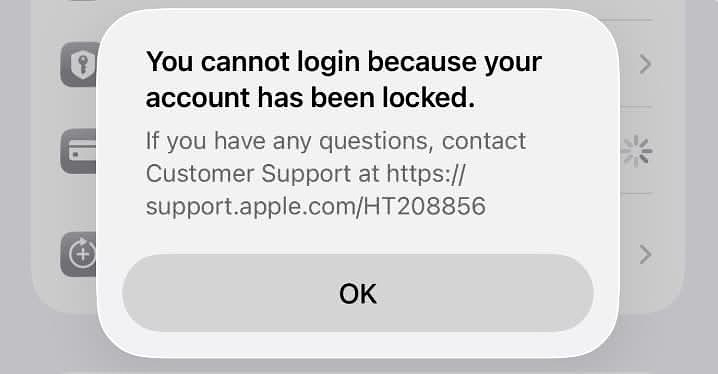

After purchasing my first phone with an aftermarket OS on it, I have basically been doing the same thing to every phone I've owned since, especially because those phones would otherwise have reached the limit of their manufacturer OS updates, and instead, I can merrily roll along on old hardware until the things physically give out themselves. They do sometimes complain when I try to do things like play Pokemon Go on them, but it's fine. And by the time I have to be in the market for a new phone again, so many of the flagships of a previous time will have come down in price to the point where I might consider them, or consider asking for them as holiday gifts from people who like to spend money on me, despite my clear failures at capitalism.

So as a cheapskate with regard to technology, it's always nice when I can take the old things and make them run smoothly and swiftly with new software or by respecting their limitations enough to not tax them with software that's not suited to them. (One of my next projects, whenever I have actual need to do so, is to do some exploration of software that can be run from the terminal, so that my spare Model B won't feel left out from the fun and can contribute to some important part of house functions.) That cheapskate nature meant that when I got to examine the original model of Chromebook, and was told that I could do what I wanted with it, since the original model Chromebook stopped receiving updates at Chrome 65, I consulted the Internet, and while there wasn't much information available, there was a website that was dedicated to the prospect of converting such a Chromebook into a fully-fledged Linux machine by replacing the firmware on it with a specific kind of compatible BIOS, and then from there making it possible to put a Linux on it. (It's a very nice machine, actually - 64-bit, a couple gigabytes of RAM, and a 5GHz-compatible network card internally.) Well, I should say the website existed at some point in time, but didn't actually do so at the moment I set my mind to it. Thankfully, the Internet Archive had crawled the entire thing, and I could download it into a zip file, giving me the opportunity to follow the instructions and examine the pictures. I was initially stymied by the first instruction of turning the developer switch on, because I couldn't see a developer switch in the spot where the pictures said it was, but once I discovered that it was behind a small bit of electrical tape, we were ready to go. (That piece of electrical tape would come in handy later, as the thing that was used to disable the write protection on the firmware on the laptop.)

Again, low stakes project, no worries if things didn't go according to plan, because it was otherwise not being used, and great potential for use if it succeeds. Which it did! I followed the recipe exactly as the website archive instructed, got the new BIOS in it, and then put a Chromebook-related Linux on it, boggling the developers of it, because their Linux was not meant for a Chromebook that old. They weren't even sure it would run on it, despite me showing up with such a thing. Eventually, I scrapped that project, since it hadn't updated in a very long time, and instead went with the distribution that was powering one of the "spare" work machines that had been designed with Windows XP in mind and had fallen out of use as a mobile reference tool. I had been using those machines for all kinds of shenanigans and other material that official machines were not being used for, and they have served me well, even if only one of the original pair survives.

That Chromebook still runs BunsenLabs, and does so wonderfully. So long as I don't try to tax it too hard by running too many tabs on it, it rewards me with snappiness and speed, and most importantly, a system that can be updated and kept patched against security vulnerabilities. (When the second of the pair of netbooks finally refuses to boot, this Chromebook will likely take its place as machine-outside-of-boundaries.) And having done it once, when I was alerted to the possibility of getting another Chromebook of a later parlance for a little bit of nothing and doing the same thing to it, I jumped at the chance, and with a similar sort of process, and using some scripts developed by others, I now have a compact and useful Linux laptop that I do a lot of composition on, and that I can take with me to events like the local GNU/Linux conference so I can do interactive bits, or run programs, or just hang out in the chat rooms and post on social media my running commentaries about the sessions that I'm listening to. I've also used it as a presentation machine for such things, when I'm the one doing the presenting instead of listening. After trying to run a form of Arch on this Chromebook, and eventually running into the problem of install creep and strict size limitations (as well as the nasty tendency for it to hard freeze at some point when it ran out of memory and swap), I put BunsenLabs on it during this last update cycle, and it's much happier with me and seems to function better. We'll see what happens when BunsenLabs finally makes the jump to a Trixie base instead of a Bookworm one, but I feel pretty confident I'll be able to get all of that to work, and it'll be nice to have old hardware running modern systems.

I'm doing this because of the work that other people have done to port boot systems to Chromebooks and other machines, and to automate the process of installing things to the right places, and the people who build and maintain the packages and the installers so that all I have to do is download the image, run it, install, and then run the update commands on first boot to get to a system that's ready to work. It doesn't feel like computer touchery to do this, because it's just using other people's stuff, but there's the tale of knowing where to make the chalk mark as one side of it, and the other being whatever arguments you want to bring to bear about how "not invented here" is terrible as a practice, and therefore if someone else has created the thing that you want to use, use the thing they've created and spare yourself the turmoil. (Or, in my case, use the thing because you couldn't create it yourself anyway, and be grateful to the people who are using their time and knowledge to make it so that you can do this thing.) Doing things in userspace is still valid, and as an information professional, a lot of my skills are in finding and surfacing the thing that will be useful for the situation, rather than in trying to create the thing completely from scratch, or in trying to get the person I'm helping to do the same. The world is too large and complex for any one person to understand, or even to necessarily understand the entirety of their discipline, and so it should not be a mark of shame to rely on the work of others and to trust that their work will be accurate and not malicious. (It just makes me feel much more like a script kiddie playing in the kiddie pool instead of a Real True Technologist, even if this is another one of those situations where if you press me on the matter and start making me tell stories and explain myself and solve problems, the claims I'm making look flimsier and flimsier, a fig leaf of modesty because I'm still afraid of the reaper looking for tall flowers.)

There's a lot that I have done, and that I can and should justly consider as achievements and Cool Things. Doing things like December Days and the Snowflake / Sunshine Challenges and other such writing prompts are my way of indirectly getting at those and showing them to others. If I came out and said it directly, I'd be worried about it sounding like boasting or penis size comparison, and someone else would come along to put me in my place. But if I'm talking about how there's a wealth of software and instructions out there to extend the life of old technology, and I'm a cheapskate who's willing to invest the time in following those instructions and prolonging the life of that old technology, it doesn't sound like I'm boasting about anything other than getting some extra cycles out of my machines, and that is something I can safely be proud of. (Why? It's not saying I have any particular skills or capacities, just that I know where to look and how to follow recipes.) Indirectness is one of the best ways to get me to show you my actual potential and abilities, and I can do it to myself just as well as anyone. Full understanding may need a little bit of either reading between the lines or knowing me well enough to see what I'm doing, or to ask the right question that makes me squirm or tell stories. (Please do.)